Article By: Wendy Graves via Hockey Canada

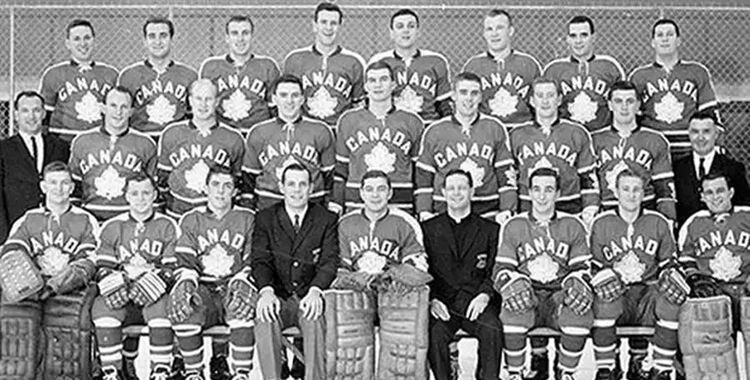

It has been 50 years since Canada’s National Men’s Team first stepped onto the ice at the 1964 Olympic Winter Games in Innsbruck, Austria.

For the first nine Games, Canada’s best amateur team had represented the country. But after a disappointing bronze in 1956 and silver in 1960, it appeared that international teams had not only caught up to but passed the country’s top club teams.

Father David Bauer, then the headmaster at St. Michael’s College in Toronto and himself an accomplished hockey player, felt Canada needed its own all-star team.

At the 1962 Canadian Amateur Hockey Association (CAHA) summer meeting, he proposed his idea: a team comprised of the best university players, training together a season in advance at one of Canada’s campuses. The CAHA approved Bauer’s idea, but he soon discovered he needed more than moral support. He needed more money.

In a letter to Judy LaMarsh, then the minister of national health and welfare, Bauer asked for assistance in helping Canada build its first national team. The cost of financing the 1956 and 1960 Olympic teams, plus the teams sent to the IIHF World Championship from 1961 to 1963, had left the CAHA’s cupboards bare. Pre- and post-Olympic tours would bring back about $30,000 in revenue, but that still left the group about $21,000 short.

Bauer appealed to the minister’s national pride in his request. “In entering this new program, the CAHA felt we would be able to supply a Canadian team that was (a) truly national in composition, (b) clear of any possible stigma of professionalism, and (c) capable of adequately representing Canada and possibly winning back the Olympic hockey crown for our country.”

In November 1963, the National Fitness Council granted Bauer $25,000. In giving the money, the chairman indicated the council’s support for “a fully national venture by an amateur team.” The council asked to be kept in the loop on how the team was doing so that any additional funding requests could be quickly considered.

By this time, Bauer was at the University of British Columbia and his players were enrolled in their first semester at the school. After six weeks of practice, the team embarked on a 33-game exhibition schedule that included stops in Chilliwack, B.C., Drumheller, Alta., Estevan, Sask., Flin Flon, Man., and parts in between. The team wrapped up its cross-country tour against the Toronto Marlies at Maple Leaf Gardens on Jan. 5, 1964, losing only eight times along the way.

The Canadians flew to Europe the next day for a 10-game exhibition tour. They finished with a 5-4-1 record playing teams from Germany, the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia.

Defenceman Rod Seiling had played against international teams before. “I had a bit of inkling how much of an honour it is to represent your country, but nothing prepares you for the feeling you get when you get into the Olympic Village and you’re representing Canada,” he says. He also knew his country was watching and expecting big things. “You understand quickly the responsibility that comes with [playing hockey for Canada].”

While the European exhibition results were underwhelming, once the Games arrived, so did the team’s stride. It opened with five straight wins, defeating Switzerland, Sweden, Germany, the United States and Finland by a combined score of 29-11.

In its next game, Canada led Czechoslovakia 1-0 after two periods, thanks to a goal from Seiling. With less than 10 minutes to go, a Czech player collided with Canadian goalie Seth Martin, leaving Martin clutching his knee and needing to leave the game minutes later. With no chance to warm up, backup Ken Broderick surrendered three goals in eight minutes. The loss left both teams with 5-1 records.

The medal chase came down to the final round robin games: Canada against the undefeated Soviets; Czechoslovakia versus Sweden (4-2).

George Swarbrick gave Canada a 1-0 lead after one period. The Soviets tied it up midway through the second, but Bob Forhan quickly restored Canada’s lead. With less than two minutes to go in the period, the Soviets struck again and the teams headed to the final 20 minutes tied at two. Looking to give his team a spark, Bauer pulled Broderick for Martin, who had been sensational in net before getting injured in the previous game. Martin surrendered a goal on the first shot he faced, but proceeded to stop the next 18 the Soviets sent his way. Alas, the Canadians could not find the equalizer – they managed only 17 shots on net in the game – and lost, 3-2.

The defeat left the team deflated, but at least it would not be going home empty-handed – or so it thought.

With a perfect 7-0 record the Soviet Union was the new Olympic champion. Canada finished with a record of 5-2 and in a three-way tie with Sweden and Czechoslovakia. The tie-breaker rules, as Canadian officials understood them, meant Sweden would get the silver medal based on a better goal differential in games against the top four teams; they were +1 in games against the Canadians, Czechs and Soviets. Canada (-1) would be awarded the bronze over Czechoslovakia (-5).

But during the third period of the Sweden-Czechoslovakia game – a game Sweden went on to win 8-3 – IIHF officials met and changed the game plan. Ties in the standings would be broken by goal differential against all teams, not just those in medal positions. Sweden stayed in the silver medal position (+31), but the sudden rule switch meant Canada (+15) and Czechoslovakia (+19) switched spots. Canada was now fourth and out of the medals for the first time at the Olympics.

Not knowing this, the players went to the Olympic Stadium to get their medals. In an interview with the Hockey Hall of Fame, forward Brian Conacher recalled getting the news: “After being robbed of a medal, [forward] Marshall Johnston turned to Father Bauer and said, ‘It looks, Father, as if the shepherd and his flock have been fleeced.’”

With nothing left to collect, Bauer led his team out of the medal ceremony.

The backroom deal orchestrated by IIHF president Bunny Ahearne tainted an otherwise positive Olympic experience for the players. “It leaves a sour taste as an after-effect,” says Seiling. “It doesn’t detract from the friendships I made – through the experience and the experience itself, I would never want to give that up. It just didn’t end up like it could’ve or should’ve.”

Visit HockeySask.ca

Visit HockeySask.ca